Most people’s relationship to Investment Management is a bit like their relationship to Technology: we just want it to work for us. Yet when it doesn’t, more often than not we simply shrug our shoulders and move on. At first sight this behaviour seems odd. Surely there is little more important than ensuring a stable financial future? but as the rise in passive investments seems to attest, the vast majority of investors seem to simply accept the reality of their (often disappointing) returns.

To be fair, those with exposure to Active Managers have been voting with their feet and walking away from poor returns, but this is more a factor of what are seen to be unrealistic fee levels for lacklustre performance than a (poor) return-based decision. Relatively few investors are doing line-item examinations of portfolio holdings or returns any more than we spend our free time clearing out data caches on our mobile devices or set timers to maximise charging efficiency on our ‘phones. Rightly, or wrongly, we just expect it to work. Sure, we can ask the “why did you (we) underperform the market/competition?” question, or challenge on fees, but in the same way that we seem to accept that our ‘phone battery no longer lasts as long as it did or that the 5G data coverage seems to get worse not better over time, for the most part, anything short of a debacle is grudgingly accepted and we move on.

Avoid risk and manage uncertainty

However, it is the role of investment BIAS in this process that is the Elephant in the room. One of the reasons why we don’t challenge things more is because we tend not to recognise that Investment Management is structurally misaligned with our own perceptions of what we are seeking to achieve. Most investors are seeking something very straightforward – they are looking to compound their returns over time so as to maximise their wealth. In investment management speak – “…they are seeking to maximise the time-average growth rate of their investments”. The reason that Investment Management often doesn’t seem to work very well for investors is that the regulated model that most investment firms follow does not target this at all. Expected returns – not compound returns -are what is optimised/maximised in their investment processes. This is the BIAS that we need to address.

Maximising returns is not the same as maximising wealth

This distinction is subtle but important. To maximise expected gains from investment exposure is not the same as maximising wealth. Indeed, the opposite is likely to be true: as the degree of leverage applied scales, the investor exposure to risk increases exponentially with any increase in overall wealth[1]. The way that this is carried out is also important. Investment managers typically operate with either an expected return target such as a positive real return or to outperform an index under a given set of risk constraints, or a straightforward maximisation of expected returns, given a predetermined set of risk constraints. Either way, the role played by the determination of client risk aversion in the form of helping to define those risk constraints is central to the Financial Advisory and Investment Management industries.

Establishing those constraints is one of the first things that any regulated financial advisor is required to determine. For any new client, their level of risk aversion is the key KYC data point – the greater it is, the more the advisor will shy away from risk in terms of exposure to investment risk via a “risky” asset or group of assets. The determination of this measure is normally conducted via a survey process (age, existing assets, number of dependents, current and planned levels of expenditure etc.) that then leads to a risk categorisation and an investment solution proposal from the advisor. The “60/40” Equity/Bond portfolio is the classic “toy” example of this, with the equity component being deemed the “risky asset”.

And that’s it. The investor’s risk appetite is “set”, and an investment portfolio is structured to provide the agreed level of leverage (exposure) to the risky assets in order to maximise the expected investment gains. Except that’s not it. The reality is that the survey approach is unlikely to provide a credible form of quantification of risk aversion; most investors are relatively poor at identifying their own initial level of the somewhat abstract concept of risk aversion and certainly not in the context of a multi-year time frame. There is strong evidence that risk aversion is a dynamic feature of human behaviour and changes with both time and levels of wealth – neither of which is really considered in the “one and done” risk categorisation approach of the advisory industry.

Risk is not a simple measure

Beyond this, a lower level of exposure to a ‘risky” asset does not mean that there is no exposure to risk beyond the risky asset. Short of holding cash, all other assets within a portfolio will also involve a level of risk – it’s just that these “risks” may be less well articulated than a simplistic measure of risk such as “the volatility of returns”. Risks to an investment can take the form of other risks that are not easily managed via portfolio construction such as leverage, liquidity, transparency, expense (fees) or complexity. More importantly, neither the investor nor the Investment Manager are likely to be able to properly account for these “risks” in relation to a perceived level of investor risk aversion. Treating risk as simply a factor of investment reality and extending the idea of a “risk free asset” from financial theory to portfolio reality is dangerous to your wealth.

The first thing to consider is what the investor level of risk exposure actually is. The use of the term “Risk” throughout this piece has been in inverted commas for a reason. The generic nature of “risk” as a term obscures the very different elements that impact on the investment decision making process and the importance of not only recognising these differences but employing a range of different strategies to help to manage them.

In a recent post we made the point about the importance of the definitions of Risk and Uncertainty in relation to financial markets:

“Risk is a situation where there may not be a fully known outcome but there are a known range of probabilities for a range of possible outcomes and the probability distribution is therefore understood. Uncertainty is where not only is the outcome unknown but the probabilities of the range of possible outcomes are also unknown. This is not to say that there is no information available – it’s just that the exact probability distribution is not known.”

The former we would argue is something that is actively engaged with whilst the latter is something that can only be managed. In either case, it makes sense to only expose capital to risk or uncertainty where it is unavoidable to do so. Making an active decision to not be exposed to any avoidable risk is a far more rational start point than thinking that somehow diversifying risk across a range of different risks is somehow managing or mitigating risk exposure. How is adding liquidity risk to a portfolio via “diversifying” from public into private equity really a risk reduction strategy? Spoiler alert: it isn’t. All you are doing is complicating the number of risk decisions that you are simultaneously taking with a (likely) deleterious effect on long term wealth!

Unknown Knowns

Most people are familiar with the 2002 framing of information by the then US Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld into the categories of Known Knowns – things we know we know and understand, Known Unknowns – things we know exist but don’t have full knowledge of, and Unknown Unknowns – things that we don’t know that we don’t know. However, there is a fourth category – the Unknown Knowns. These are things that we do know (or are known by others) but either choose to ignore or deny to ourselves. And in decision making, these are the most important information things of all.

To put this in the context of investment and decision making, we can construct what is known as The Rumsfeld Matrix and categorise the quadrants by way of familiar decision vectors in investment management.

- Known Knowns: These are facts or variables that we’re aware of and understand. RISK

- Known Unknowns: These are factors we know exist, but don’t fully understand.

UNCERTAINTY

- Unknown Unknowns: These are factors that we’re not aware of and can’t predict.

BLACK SWANS

- Unknown Knowns: These are elements that we don’t realize we know.

BIAS

Categorising the first three of these in terms of Risk, Uncertainty and Black Swans is designed to help frame the Investment Management decision process.

Our Known Knowns are the Risk decisions that form the foundation of the process. The key here is to NOT TAKE Risks that are known but AVOIDABLE.

Our Known Unknowns are the Uncertainties associated with our investment selections. We may have an expected return forecast for an asset, but it will come with a range of probabilities with respect to that forecast. The key here is to be as robust in estimating these probabilities as possible but to employ techniques such as diversification to MANAGE

the elements of the investment process that are known but UNAVOIDABLE.

Our Unknown Unknowns – our “Black Swans” to adopt Nasim Taleb’s famous phrase -are the elements of the investment return process where predictive capabilities are minimal or non-existent. These are not Black Swans in the true sense of the term since we do have past experience of what statisticians refer to as “Tail-risk” events – most recently in April 2025. However, it is because the capacity to anticipate their emergence is limited, it requires the existence of tools to HEDGE against their sudden emergence such that the impact of UNAVOIDABLE negative tail risk is at least MITIGATED.

Declare your Biases

It should be clear by now why I’ve categorised the Unknown Knowns category as BIAS in the context of this investment process. Failure to proactively address bias in investment decision making is what leads to lazy acceptance of the Status Quo. It allows for the perception that Market Cap weighting is a “Risk” Management tool or that Factor categorisation provides the ability to offset sub-portfolios (of Value and Growth for example) and reduce “Risk” by doing so. It also means that the Investment Industry shibboleths of Multi-Asset portfolios, adoption of alternatives as diversifiers or the use of price volatility as a credible measure of “Risk” in a portfolio become embedded norms as opposed to misleading propositions as to how an investors’ money is best managed. It is these industry biases that need to be addressed before the investor’s ambitions can be realised.

There’s no need to “take on” risk to manage returns

As we have already outlined, simple return objectives such as “beating cash”, achieving a positive real return ahead of inflation or achieving a return ahead of a benchmark index come with an associated “risk constraint”. In reality risk constraints (or the lack thereof) on Investments related to liquidity, transparency, expense (fees), complexity or leverage are all constraints that are, in fact, exogenous to the investment return decision. Some of these constraints may be relatively benign but others can impose risks that not all investors may wish to be exposed to. So as with the private equity example, there may be little benefit to a wealth maximising investor to be exposed to the high risk/high reward opportunities associated with alternative investments if they pose a non-linear risk to wealth preservation and growth.

This is where the external risk constraints of the fund Manager’s investment strategy matter and where their inherent BIAS needs to be recognised and (potentially) rejected. The classic “benchmarking” constraint is an example of this where tracking error is used as a measurement of “active risk” by the Investment Manager, but by recognising it as a BIAS we can also treat it as a limiting factor on the ability to compound returns given the often Market-Cap weighting construction of the benchmark concerned. Being required to effectively track exposure to the Mag-7 is an example of this problem. What is perceived to be a risk mitigating factor (not underperforming the large Cap benchmark) is requiring the investor to take significant, correlated exposure to a group of stocks whose collective returns have the capacity to not only provide growth, but to also destroy wealth over time. This is an AVOIDABLE risk that needs to be recognised as such.

As far as these other constraints are concerned the case can be made that none of the risk constraints described above should really be removed – no illiquid ,expensive, leveraged, complex or non-transparent assets need to be added to the risk exposure of the investor. Failure to reject these would simply expose the investor to AVOIDABLE risks. The case made in our recent commentary Building blocks for the inability of non – equity components of a multi-asset class portfolio to provide risk diversification away from the underlying Equity Factor risk exposure is another example of this. It highlights the need to manage any risk as a simple component of portfolio construction – by simply not engaging with these additional risks in the first place and is central to our approach that “all you need is equities”.

Having rejected the idea that Risk is unavoidable, we can focus upon how to manage those elements of uncertainty and exposure related to the portfolio construction process that are unavoidable in order to manage and mitigate their impacts.

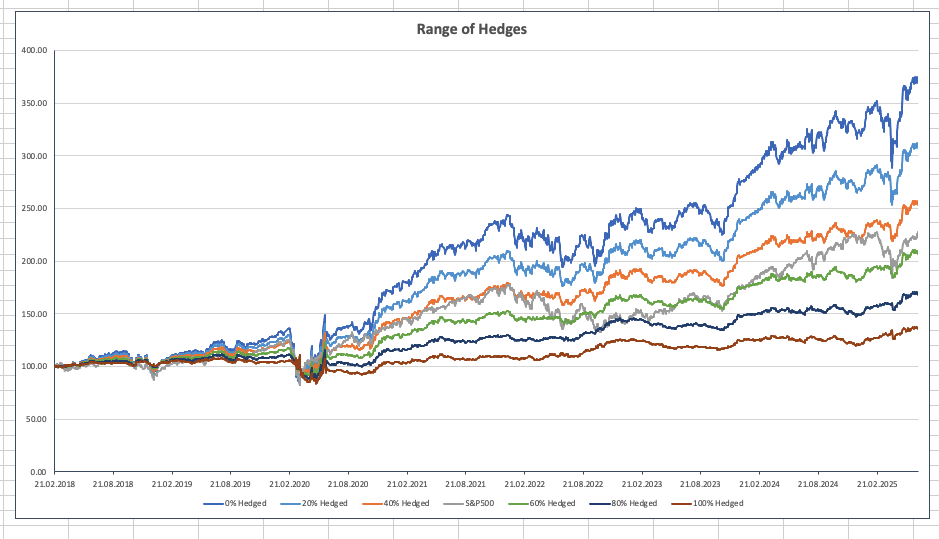

The chart and tables below show one way in which the Libra Smart Alpha product is able to provide this kind of management of uncertainty and tail risk. Starting with an equity long-only portfolio selected from the point-in-time membership of the S&P 500 index constituents and following the Libra Smart Alpha methodology , we are not concerned with the external risks of adding non equity factor risk in terms of a multi-factor portfolio approach, whilst the use of the S&P500 as a selectable universe only means that there are no additional risks taken with regard to liquidity, transparency, benchmarking or complexity The only thing we need to manage and mitigate are the uncertainties contained in the portfolio process itself.

We do this as follows:

- Concentration risk is managed via stock level diversification holding 48 equal-weighted stocks.

- Autocorrelation and information change (news) is managed via a rebalance every two months.

- Factor exposures are rebalanced to be factor neutral (Deep Value, Value, Quality and Growth) every two months in order to mitigate against emerging Factor bias.

- Tail risk exposure is mitigated via a leveraged hedged position in an ETP net short position in the S&P500 as described in the Building blocks piece.

The chart and table show how this last point in particular can be used to adjust the Long only portfolio to be hedged with point 4 to varying degrees as outlined in the Building blocks commentary. The period concerned is from February 2018 to 26 June 2025 and the data in the tables reflect the returns across the entire period. This, of course includes the COVID period that has now dropped out of the % year relative data set so the last two rows of max min numbers that are included refer to the last 5 years only.

Conclusions

Investment decisions should be the process outcome of the risk matrix that we use There are three steps to this. Rather than simply accepting the status quo at either the product or the process level , step one is to simply reject all risks that are avoidable. This means that externally determined risks (liquidity, transparency, complexity etc.) and including multi asset risk exposure can simply be removed from the investment decision and the potential universe of investible assets identified.

Step two is to construct a portfolio from that universe utilising the highest level of information available to narrow down and select assets that are designed to work at a portfolio level to explicitly compound wealth over time. This means that expected returns are not the optimal selection process but that the uncertainty relating to those returns is an explicit part of the selection decision. This includes a deliberate decision to use investment Factors as a categorisation process; making sure that no unintended factor Bias exists as part of the selection process.

Step three is to structure the Equity portfolio in such a way as to ensure that tail risk can be actively hedged. Rather than relying on the supposed non-correlation of bonds to equities to manage and mitigate against this, the best way to hedge the risk of a negative market event is to be “short” the beta of the market itself via a short position in the S&P500. The degree to which the hedge exists can be approximated in the language of the hedge percentages in the table, so the default “60/40” portfolio of Investment Management is the 40% hedged portfolio column, whilst the aggressive “80/20” is the 20% hedged portfolio column and so on. What we referred to as the “pure Alpha portfolio in the Building blocks piece is the 100% hedged column.

With this approach, the wealth manager can simply map his client’s “Risk Aversion” to the

annualised growth required by their investor such that they are able “to maximise the time-average growth rate of their investments”. By the simple adjustment of the hedge parameter, a single, long equity portfolio can be adjusted dynamically to map to the changing level of a client’s risk aversion over time to ensure that their client’s goal of Wealth Maximisation is achieved at the lowest level of risk possible.

[1] A good discussion of the problem with wealth maximisation can be found here: https://ergodicityeconomics.com/2025/05/28/expected-utility-maximizers-dont-maximize-utility/