Part 1 – Time to explain

Yet again, the financial industry has had to start the year on the back foot. As lists of dramatic fund level underperformances circulate in the media, the explanations, rationalisations and justifications for failure are being delivered via fund reports and year ahead presentations. However, the bigger issue that is emerging is far more significant and important than one-year’s investment return. What has been revealed is that there is a structural flaw at the heart of the investment industry’s approach to portfolio construction and risk management that cannot be glossed over or ignored. The industry needs to not only understand what that flaw is but needs to be able to fix it.

Tell me why I should believe you?

Investor confidence in investment managers is low and what might have looked at the start of the year to be a relatively familiar process of ex-post explanations and “mea culpa’s” as to why 60:40 funds had one of their worst years ever or how the majority of ETFs and tracker funds (and, let’s not forget, most active managers) across the spectrum saw significant double-digit declines over the course of 2022, this time it really is different. It is going to require something more than a simple apology for losing your money. As markets acknowledge that the era of zero interest rates is over, they are also beginning to recognise that most – if not all – of the other macro assumptions of the last decade have changed. Inflation expectations, supply chain logistics, geo-politics and changing global trade patterns, commodities, currency-blocks, credit cycles – none of these will look the same over the next few years and are likely to be dramatically at odds to what we experienced since the 2008 financial crisis.

As a result, investment managers are going to need to explain not only how they performed (or not) in 2022 but how their existing investment processes can successfully operate going forward. Simply put – given the macro realities of last year and the implications that these developments may now have for future market conditions – are these (existing) investment processes fit for purpose? Can they adapt and change to a very different world in 2023 and beyond?

The outlook is not good. With the exception of a few macro trading funds, the whole investment industry appeared unable to cope with the investment environment in 2022. These macro “asset allocators” will doubtless declare victory over their peers but it is not really about why they “won” but rather why almost everyone else lost. Moreover, even if 2022 can be put down to an exceptional set of circumstances, any attempt to justify poor performance on the basis of this being a “one-off” macro shock would be to ignore the aftershocks that events in 2022 are now imparting on the entire global economic system. Just how confident investment managers are about how to navigate the future depends on how they currently approach the topic of portfolio construction and risk management. The widespread nature of recent losses and extent of future macro uncertainties suggests that there may be a more structural issue in need of investigation. We need an inquiry.

You had one job…

Rather than seeking to understand “How” the investment industry managed to lose quite so much of your money in 2022, the first question for an inquiry is probably better expressed as to “Why” it happened. Pointing as we have in the past to the dramatic shift in the monetary backdrop last year as global developed market interest rates were driven higher (along with the inflationary aftershocks of COVID lockdown and spiking energy costs) is clearly a causal explanation as to why markets sold off in the manner that they did but it does raise the question as to whether there was, perhaps, a better portfolio solution that could have been pursued in order to manage such macro externalities. At the heart of the inquiry is the question as to whether portfolio risk and reward is properly structured for now and in the future.

In truth, passive investing involves investing on the basis of the future investment environment being essentially the same as the past – whilst simultaneously warning in the investment disclaimer that past performance is no guarantee of future results.

For the passive end of the spectrum the answer to this is no. And that’s a bit of a problem. Passive funds may provide the low-cost alternative for maintaining and tracking market exposure but when the major market benchmarks are sliding by 20-30%, your portfolio simply follows suit. Passive investment cannot handle market shocks. In truth, passive investing involves investing on the basis of the future investment environment being essentially the same as the past – whilst simultaneously warning in the investment disclaimer that past performance is no guarantee of future results. This is the existential dilemma that the industry seeks to avoid having to confront but that circumstance dictates it is constantly having to face. Pure tracker or passive funds are structured as replicants of historically representative benchmarks or universes that are basically expected to operate in the future as they did in the past, all other things being equal. However, when US interest rates rose from 0.4% (essentially the level of the last decade) to 4.4% over the course of 2022, the impact on liquidity and the money supply was dramatic and all other things were very much NOT equal. As such, any assumptions based upon prior normality couldn’t fail to disappoint.

Structural deficits…

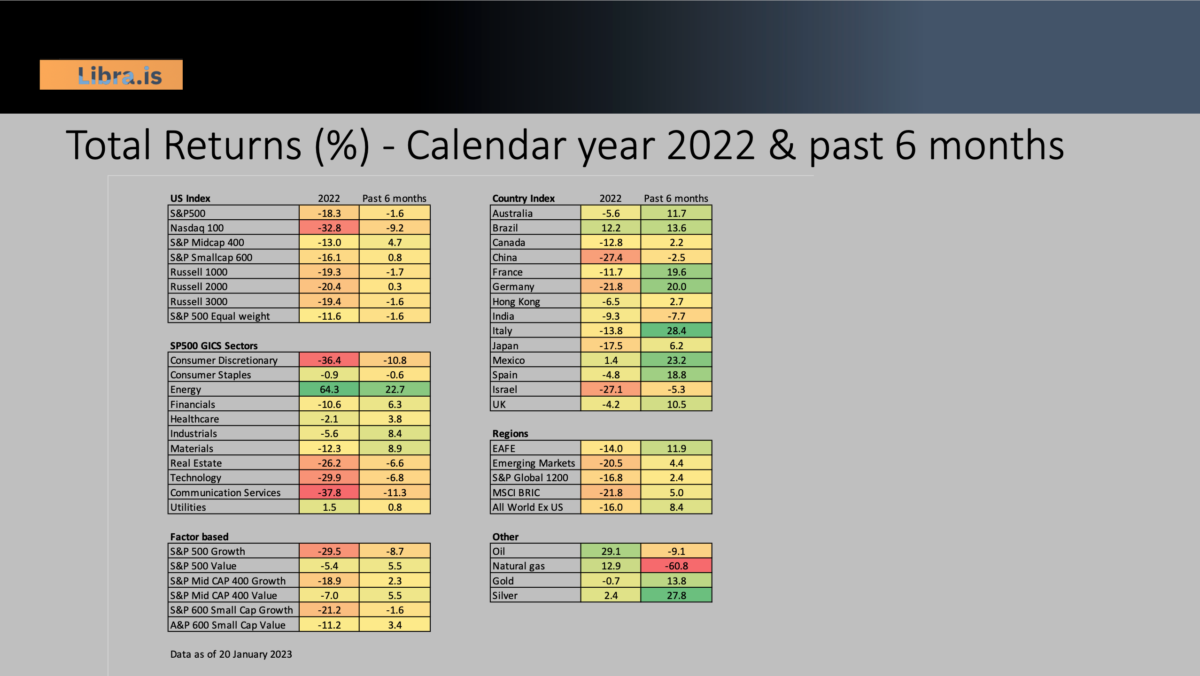

Pre-determined thematic baskets, sectoral indices, and structured products in general (including their ETF derivatives) faced a similar problem. With the clear exception of Energy (up 64%) and Utilities (1.5%), all other (US) related sectors were down in 2022 (Communication Services being -38%). For Sector baskets, categorisation is not really a problem at the broad level (an Energy stock is going to remain an Energy stock) but what about “clean energy” versus “fossil fuel based energy”? How are the internal boundaries determined and by whom? Should sub-sector baskets be created on the basis of perceived environmental risk or investment return? These are now known issues that need to be addressed by the industry and add to the requirement for adaptive portfolio construction approaches to be designed and implemented.

Style or stylised?

The final category to consider are the so-called style related indices and ETFs (Value, Growth, Min-vol, Small Cap etc.). Whilst their intellectual underpinnings imply a more discrete and diversified range of potential outcomes aligned to investment factor returns with divergent (and therefore non-correlated) outcomes, in reality they provided less in the way of risk management than might have been required given headline factor returns. In 2022 these ranged from (-30%) for SP500 growth (dragged down by “Mega Cap” and Tech) to (-5%) for S&P 500 Value (boosted by Energy stocks). Mid-Cap outperformed both big and Small-Cap growth, but Big-Cap value outperformed both Mid and Small-Cap value. So, was the driver of Energy a positive Value trade and the decline in Tech and Consumer discretionary an anti-Growth trade? Was size a negative factor for Growth but not a significant factor for Value? Could factor based products have been used to construct a risk managed portfolio for 2022 and, if so, can that still work in 2023?

The problem for many Factor-based products is that, much like their Market or Index based counterparts, they remain formulaic in structure; all of these approaches to investment require the tracking of a predetermined basket of stocks that, even though their memberships do change over time, are not especially dynamic in nature. The membership rules and index constituents are provided by Index companies – not investment management professionals. These constituents are periodically reviewed – but to a timetable – not based on changing market conditions. As to whether it is these concepts of Growth, Value and size that were the relevant drivers of returns in 2022 and in the future – as opposed to clear structural sectoral and economic factors? In 2023 that case needs to be made.

If there is one easy lesson to be learnt, it is that this inability to adapt to changing external environments is a major flaw in the Structured Product world that cannot be fixed by a simple change of benchmark, style or approach. It requires structural reform.

In Part II of this inquiry, I will review the Passive to Active investment spectrum in more detail and examine how these structured products have actually proved to be structural constraints. I will also discuss how the need for more dynamic solutions for portfolio construction and risk management in the future are going to require a permanent shift from a passive to a systematic active investment approach and what that solution should look like.